Comments by Drs. Sally & Bennett Shaywtiz on Dyslexia & ADAAA

Washington, DC:. Sally Shaywitz, MD, center, talking with Representatives Rob Andrews (D-NJ), at left, and Joe Courtney (D-CT), at right.

Summary of comments of:

Dr. Sally Shaywitz,

The Audrey G. Ratner Professor of Learning Development at Yale University School of Medicine

Dr. Bennett Shaywitz,

Charles and Helen Schwab Professor in Dyslexia and Learning Development, Chief, Child Neurology, Professor of Pediatrics and Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine

ADA Background:

- Create a level playing field between people with disabilities and those without disabilities, to the degree that reasonable accommodations can do so (e.g., curbcut where a minor adjustment in pouring of concrete can permit the wheelchair-bound to cross a street; fairly minor accommodations allow the blind and deaf to take standardized tests in ways that let them compete fairly with the nondisabled).

- Disabilities may be obvious and mechanical — being in a wheelchair.

- Disability also may lie in way that a brain functions — as in the case of dyslexia — where part of the brain that is engaged in act of automatic reading functions differently than for nondyslexics.

ADA and Cognitive/Mental Disabilities:

- ADA does not intend to alter admissions standards at Harvard or UCSD, or the GPA needed to graduate from high school.

- ADA does permit people of similar intelligence and potential to compete more fairly for achievement in education and the workplace, even if one is disabled.

- No logical reason why ADA should not level the playing field for both those with physical disabilities and those whose brains function differently.

- ADA cannot, and is not intended to, alter standards for those with different brain functions.

- What ADA can and should do is to eliminate testing and other protocols that tend to report as less intelligent or less capable those who are in fact merely disabled but can ultimately perform tasks, focus, feel and reason to the same degree as others who are not disabled in this way.

- Tests that specifically penalize dyslexics are like curbs that wheelchairs cannot get over; they are an unfair and inaccurate measure that blocks achievement and advancement of otherwise capable people.

Why we care about the ADA and dyslexia:

- Tests that specifically penalize dyslexics not only lead to inaccurate downgrading of the seeming intelligence of a person with this condition, but also can cause others to overlook the particularly advanced and distinctive nature of the creative faculty in dyslexics.

- Science is zeroing in on the discovery that, just as dyslexia impairs the speed of reading, it also expands the capabilities of other parts of the brain, releasing creativity that may be blocked in nondyslexics.

- Just as someone wheelchair-bound develops a stronger upper body, a dyslexic may have more capability in certain tasks than a nondyslexic.

- Standardized tests that fail to accommodate dyslexics and fail to report this distinction lead to a general societal failure to benefit from the talents and skills of all members of society and cause a tremendous loss of needed human capital.

- Legislative changes to ADA should reflect scientific advances of all kinds:

- Discovery of the special talents of the dyslexic

- Revision of standardized tests and certain testing protocols to report accurately the talents and achievements of the dyslexic

- Some accommodations under ADA may not be justified by reason of:

- costs – understandably, not practical to have moving sidewalks instead of curbcuts on major streets;

- it might create an unfair bias in favor of certain conditions – (e.g., colleges should not be told to have lower admissions standards for people with disabilities).

- Issue is to measure abilities fairly and on a level playing field.

- Accommodation of extended time on standardized tests:

- allows abilities of the dyslexic to be judged fairly and accurately;

- gives people who are dyslexic an even chance to compete for success in education and for jobs with nondyslexics;

- extended time can be granted to nondyslexics without changing results in a significant way;

- time constraints are imposed for administrative convenience and are not a statistically meaningful way to evaluate intelligence or potential.

Intent of Congress to include dyslexia:

- To create a level playing field in society so that qualified men and women who are dyslexic would not be denied access to jobs because they were prevented from demonstrating their abilities.

Current interpretations of ADA exclude people who are dyslexic by:

- denying critical accommodation of extra time on high-stakes standardized tests – gatekeeper for college admission, for graduate and professional study, for certification;

- causing great suffering and loss to the individual, to his/her family, and to society;

- cruely discriminating — those with most potential, who have struggled throughout school, given up much of their childhood, worked the hardest to achieve academically and did so with provision of accommodations, are now being told because they have achieved academically they are not eligible for protection under the ADA, closing the door on years of effort and dedication and preventing access to higher education and future jobs.

WHAT SCIENCE TELLS US

Clear and compelling evidence:

- Dyslexics require extra time in order to demonstrate their knowledge and to level the playing field.

- With great effort and effective reading instruction, dyslexics can learn to read words accurately.

- Howeve, dyslexics remain slow, non-automatic readers.

- In contrast, peers learn to read both accurately and automatically (rapidly).

- Slow, effortful reading persists and characterizes dyslexic readers of all ages.

Impact of extra time for dyslexics: singular, substantial and life-altering:

- Dyslexics are inherently extremely slow readers — universal, lifelong.

- With protection of ADA and extra time:

- a dyslexic person is able to demonstrate his/her ability;

- a dyslexic person’s scores increase substantially, while a nondyslexic person’s scores increase only minimally and insignificantly).

- Without protection of ADA and denied additional time:

- a dyslexic person performs below his/her ability;

- test becomes a measure of a dyslexic person’s disability, not of his/her talents;

- denial is a barrier impeding access to jobs and careers.

Scientific evidence of the physiological need for extra time in dyslexia:

- In 1896 dyslexia is first described by British physician Pringle Morgan; but dyslexia remained a hidden disability;

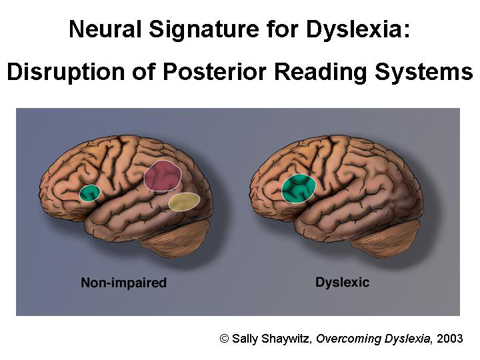

- In 2007, fMRI is able to peer inside the brain as a person reads, and brain imaging provides clear and compelling evidence that Dyslexia is real: brain systems for reading differ in typical and in dyslexic readers’ neural signature for dyslexia.

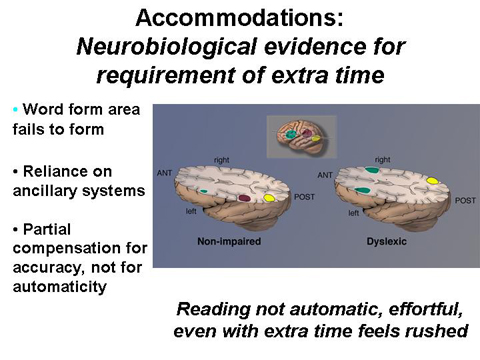

- Neural system (word-form area) for automatic, rapid reading is impaired in dyslexia; other areas provide compensation for accuracy, but not for speed.

- Dyslexia remains into adult life — neural differences remain.

- Accommodations: extra time — essential for a person who is dyslexic to demonstrate his/her knowledge.

- Accommodations critical to assure fairness and equity.

- Standardized testing agencies deny dyslexic students extra time.

- Standardized tests become gatekeeper to future: access to college, graduate and professional study, job certification depend solely on performance of these high-stakes tests.

- Failure to provide extra time to dyslexics is an act of discrimination.

WHAT CONGRESS CAN DO TO PREVENT DISCRIMINATION AND HARM TO DYSLEXIC MEN & WOMEN

- Ensure that dyslexia (slow, effortful reading) is explicitly included as an impairment in ADA restoration.

- Ensure that provision of accommodations to people who are dyslexic be required under the ADA restoration.

- Ensure that the hardest-working students who have succeeded with accommodations and do well academically are not then penalized (deemed nondisabled) and denied accommodations on high-stakes standardized tests, in turn, preventing access to college, graduate and professional education and to job certification:

- in the Americans with Disabilities Restoration Act, in considering whether a dyslexic person is limited, or substantially limited, the person shall be evaluated as compared to his/her peers;

- the Americans with Disabilities Restoration Act recognizes a person may be a person with a disability entitled to the protection of the Act, although he/she has overall been successful in school.