What I Know Now

The following appeared in the HuffPost’s Teen Blog on March 12, 2015. This amazingly well-written piece comes from an insightful high schooler with dyslexia. We were so impressed with the writing and the message from young writer Anna Koppelman that we asked to reprint it on the YCDC website. We are thankful to Anna and the Huffington Post for granting us permission to do so.

When I was in first grade, I realized I was dyslexic. My mom was in the dining room working, my dad playing indoor sock-catch with my older brother, and I was using up my one hour of TV on the children’s show, Arthur. It just so happened that at that time, on that day, the episode titled “The Boy With His Head in the Clouds” aired on my TV, which I sat gaping at from my living room couch. It was as if I saw myself on the screen.

“The Boy With His Head in the Clouds” is a 15-minute segment in which Arthur’s friend Greg (the moose) finds out he is dyslexic. He had spent years feeling behind in his class, he couldn’t read, or do math problems at the rate his peers could do them. He felt stupid and worthless, but he wasn’t. The character had unique ideas and outlooks on the world. He saw things in a different way than his classmates and there was nothing wrong with that. He was just dyslexic.

I remember hitting pause on the TV (a trick I had learned the day before) and running into my dad’s room. I interrupted the father-son sock catch, and stated loudly and a little lispy, “Daddy, I’m sisplexic!”

“You are what?” my dad responded.

I dragged him and then my mom into the living room and made them watch the show. “I have that! I have that” I kept repeating. We must have watched “The Boy With His Head in the Clouds” five times that day. In that moment the confused, innocent first grader me felt as though I had found the answer to my problems. I was no longer stupid; I just had “sisplexia” (dyslexia). But nine years, two schools and a very accommodating IEP (a legal form stating that you are dyslexic and other complicated stuff) later, I realized I could not be more wrong. One would think that being able to label your adversity makes it easier, but since that day on the couch when I realized I am dyslexic, I have increasingly felt worse about my disability.

This is me reading a picture book at the tender age of about two.

It wasn’t always this way. I used to wear my dyslexia like a badge of honor everywhere I went. In second grade, I had my teacher read Thank you, Mr. Falker (a children’s book about dyslexia) to my class, then I proceeded to tell the class I was dyslexic and what that meant to me. I was proud of it. All I could see at that point were my parents, who were always encouraging, and my older brother, who never mentioned it.

I had a tutor to help me with my reading (I still see her to this day), but to me that was just fun. We would play games on the floor of her room, and we would make sounds with letters. Sometimes she would read to me, and sometimes she would have me tell stories. School was still hard for me, counting numbers in my head was practically impossible and reading was no easy feat either. The kids in my class would be able to look at letters and see words, and I would look down only to be mystified. It wasn’t that they were backwards or in the wrong direction. The only way I could describe it is that the letters floated.

This is me at the tip of my athletic career. I was in third grade.

I was still on level 0 when the rest of my class was on level 4 and 5, but I was not ashamed of this; I didn’t realize that I had the option to be, until Emma* and close friends of mine refused to let me sit with them at lunch or play with them at recess anymore because they could read and I could not—which meant they were smart and I was not. The roof of the school was covered in fake grass, and we had tricycles that we could ride during lunch and recess. I remember watching them peddling away into the distance, with their Harry Potter books packed away in their knapsacks and thinking for the first time that I truly was stupid.

The next year I would switch to a new school (Windward) that specialized in kids with dyslexia. Throughout third and fourth grade I would learn how to read. This was not a simple task. It involved wordlist after wordlist, sound after sound, syllable after syllable, open, closed, “CCCC AAA NNN.” I have all the “classic dyslexic moments” packed away in my pocket. They involve reading my first book all the way through, being able to write a paragraph for the first time and reading aloud without stuttering. Windward cured my inability to read and helped me understand the fundamental parts of math, but there are certain parts of my dyslexia that are just impossible to “cure.” Those include my horrible grammar, sheer incompetence when it comes to spelling and the fact that certain parts of math make me want to bang my head against a wall. I am now at a mainstream school and my grades are all A’s and B+’s. I work really hard and have tons of government mandated tutoring (five hours per week). The parts of my dyslexia that used to be gigantic have shrunk—that is, all the parts except the shame.

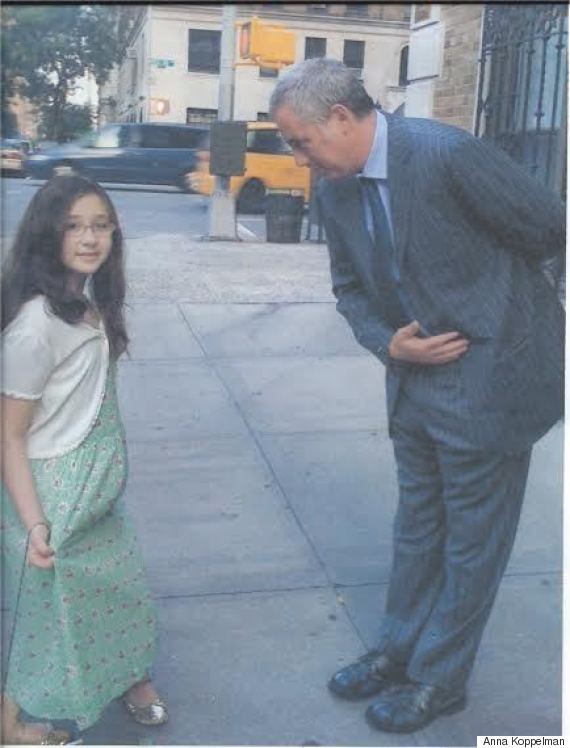

This is my dad being a gentleman and taking me out to a daddy-daughter dinner to celebrate the first book I read all the way though.

When I was younger, my parents used to be able to print out lists of famous people with dyslexia, hang it on the walls of our apartment and I would feel better. On the days that didn’t work, my mother would make me recite them: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Leonardo da Vinci, Winston Churchill. This used to help. If they could do it, I could do it, and they were living in a time when people knew way less about dyslexia. But on some days, most days, this only makes me feel worse. I could blame the teachers here and there who just didn’t understand my dyslexia (one who accused the extra time I get from the government on tests as cheating and another who said my horrible grammar would make it so I could never be a writer), but it is not their fault I feel ashamed of my dyslexia. It is also not the fault of that one 8 year-old Emma who saw someone different from her, and acted out of fear. The shame that is attached to my dyslexia is fully my fault.

A lot of the time I take the parts of learning that are still hard for me as rejection — as someone telling me I can’t. I see points taken off for misspelled words on in-class English essays, and I start to see my future crumbling. I see the colleges that my dyslexia could prohibit me from going to. I see the kids with better scores, who don’t need tutors, or extra time, and I feel jealous. I feel worthless.

High school is a world dictated by tests and grades that are made to evaluate the average mind. If you were to have a conversation with me, you would know that I am bright, but if you were to see me in the middle of a math test, you would think the opposite. I am extremely hard on myself because I am forced to see both sides of me constantly. I feel like I am living a Peter Parker-esque world. Half the time I am average, or even below average, and the other half, I shine. When my “Spiderman suit” is on (i.e. writing articles, performing poetry or talking about something I am passionate about), I feel like a superhero, or, at the very least, like I have power in me.

One in five people are dyslexic, including over 50 percent of NASA employees. I should no longer slouch in my seat in math, yelling at myself for not understanding, or scolding myself in English when the words I read aloud are incoherent. I should not measure my self-worth by what is inherently harder for me to do, but it is close to impossible not to. Dyslexia is tricky because no two brains with it are the same. My dyslexia is not your dyslexia, and neither of us should question how smart we are because we have it.

This is a picture of me the year I learned how to read. I am looking sassy in my cat-eye glasses, or at least I wished I looked sassy in my cat-eye glasses.

There is not a simple code that makes living with dyslexia easy. There is the physical part of not being able to do certain things, and then there is the limiting mental aspect in which I wrongly evaluate myself based solely on a socially constructed norm about what “smart” is. I have dyslexia and I can’t change that. Maybe I spent half an hour on 14th Street last week trying to figure out which avenue is 8th and which is 7th, and then another half trying to figure out what it meant when the nice woman walking her dog instructed me to turn left. But when I finally got to the apartment, even though I was freezing, red, and my hair was a mess, I also had a excruciatingly entertaining story about how difficult it is to walk around in New York City when you are still kinda iffy on which hand is your left.

This is my family a few months ago dropping my brother off at college and is the most recent picture of all four of us together. My hair is no longer blonde. It was a stage I went though.

While it’s hard to believe at times, I like to hope that life with dyslexia is a parable to this story. You will be stuck in the middle of a metaphorical 14th Street trying to figure out which direction is left and which is right. You will probably walk the wrong way. You will probably walk the wrong way more than once, but eventually a nice woman walking her dog (or a very special teacher) will show you the way to go, and you will work tirelessly to find the metaphorical cute boy’s apartment (and become CEO of a Fortune 500 company). I guess what I’m saying is that living dyslexic is hard, but I don’t really have a choice. The only control I have is reminding myself that I can get through it and that I will succeed. I will reach the warm apartment eventually.

*Name has been changed

Related

One Dyslexic’s Experience with Learning American Sign Language

CJ found learning ASL fairly easy. In each class he was given 45-50 vocabulary words to learn.

Read More

How Extended Time Improved More than Just Test Scores

Allison at her graduation from Columbia University, where she earned her master’s degree. Learning is not a game …

Read More

Giving Voice to a Young Person’s Dyslexia Journey

Jennifer realized she could help other kids—and their parents—by telling her own story, the story of a 12-year-old …

Read More

Life Lessons from a Lifelong Learner

Magical Thinking, Rage and Small Steps on the Dyslexia Journey By the Reverend Charles F. Harper, M.Div., Yale …

Read More