Sports: Strengthening Self Confidence and School Skills

By Nancy Hall

Parents of dyslexic young people are faced with numerous decisions as they guide their children through their school years. Is tutoring needed? How often? Summer school or summer camp? The inevitable slow reading that is dyslexia requires that children spend even more time on homework than their peers. So should parents then encourage their children to participate in sports, too?

While it’s true that all work and no play make Jack a dull boy, it also may be that all work and no play will diminish his ability to learn—and to learn with confidence.

Experts who work with dyslexic children and teens, though, agree that physical activities like individual or team sports, important for any child, are especially beneficial for those with dyslexia. Dr. Sangeeta Dey, Psy.D., who sees many such children in her career as a pediatric neuropsychologist at Northshore Children’s Hospital in Salem, Massachusetts, says that she’s delighted when she learns that a child she’s treating runs track or plays soccer or tennis. “Playing sports normalizes their experience, letting them be like other kids,” Dey says. She acknowledges that they tend to be heavily scheduled, but urges parents not to overlook the many benefits that can contribute to a child’s positive self image and may even help to improve academic performance.

Bridging a Gap

Twelve-year-old Jamie, the protagonist of Trapped, Judy Spurr’s 2007 young adult novel, struggles with dyslexia. He benefits from a special reading class, but dreads the teasing and bullying he gets over his placement there. He feels most at home on the soccer field, but he worries about keeping his mediocre grades high enough to permit him to stay on the team.

“It’s obvious,” says Spurr, who wrote the book after her many years spent as a reading teacher, “that dyslexia can lower a child’s self-esteem. For a dyslexic child, especially one who is teased by others, school is a very uncomfortable place to be.” The response Spurr got from readers of Trapped mirrored what she herself had seen: participating in sports often bridges a significant gap between the classroom experiences of dyslexic kids and what took place on the playing field.

Parent Terri Johnston tells a similar, real-life story about her son Shawn. “Even in kindergarten,” she says, “he wasn’t learning as quickly as the other kids, though he was clearly smart and eager to do well.” By fourth grade, the gap between Shawn’s obvious intelligence and his poor school performance was making him angry and frustrated.

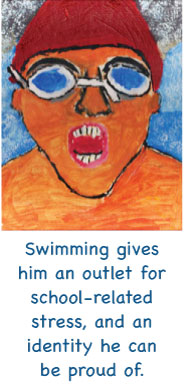

In another area, though, Shawn was excelling. “He started swimming lessons when he was 3,” Terri says. “At the pool, his skills just grew and grew. By middle school he was one of the most valuable members of the swim team and the other kids looked up to him. Now in high school, Shawn still has to work hard at reading and writing, though he gets some extra help in these areas. His mom, who supports his progress in both academics and athletics, says that swimming gives him an outlet for school-related stress, and an identity he can be proud of.

Suzie, mother of Amy, a state-ranked swimmer in New Jersey, recalls that, in swimming a tenth of a second improvement is recorded and celebrated by coaches; my daughter could immediately see her efforts rewarded with a better time. I saw the light bulb go off for her that focused effort at school would also bring improvement. She learned it first at the pool and then in school, where it took her four years to go from the lowest reading group to the highest.

Finding a Balance

Finding a Balance

“When a new family comes in, I ask them about their child’s language skills, developmental milestones, reading and writing and other academic aspects of the child’s life,” says Dr. Dey. “But I also ask about the child’s interests and other activities—what are the child’s hobbies? Does he or she play a sport or practice music or have some other creative outlet?”

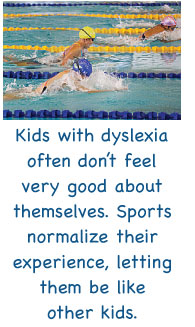

Dey says that these activities are valuable to any child, but can be especially so for a child with dyslexia. “The focus for these kids tends to be primarily on improving academic understanding and performance. Testing and accommodations offered to the child are important, but can also be very time consuming, and kids with dyslexia often don’t feel very good about themselves. Sports normalize their experience, letting them be like other kids. I always try to work appointments around kids’ sports activities because they are so important.”

Fifteen-year-old Amy recognizes the richness sports bring to her life. “I’m happy for my best friend when she gets a 100 on her English test,” she says, “even though I realize that I’m probably never going to get that kind of grade.” But Amy grins when she says, “I also recognize that she’s never going to be able to swim as fast as I can, or to bring home medals for the 200 meter breaststroke. That’s something at which I excel, and it makes my life feel more balanced.”

Teachers and other experts increasingly recognize the value of a creative and physical outlet for dyslexic kids. At the Gow School in South Wales, New York, for example, participation in athletics is built right into the school’s rigorous curriculum. Douglas Cotter, himself a Gow graduate (’87) is now assistant director of admissions and the rowing coach at Gow.

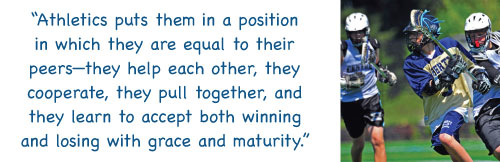

“Each boy plays two sports per year—they can choose from a list that includes rowing, soccer, lacrosse, skiing, wrestling, and several others, but they all spend time every day in these athletic pursuits. It’s a great thing for them, allowing them to excel when they may have been rather beaten up academically. In fact, there isn’t a real divide here between sports and academics—we think of the afternoon sports period as the most important part of the day. You put a ball or a lacrosse stick in a student’s hand and it’s amazing to see the confidence with which they take to these activities. Athletics puts them in a position in which they are equal to their peers—they help each other, they cooperate, they pull together, and they learn to accept both winning and losing with grace and maturity.”

A Parent’s Role

Dr. Dey encourages parents to help their children and teens find a space in their lives for sports. “Let your children guide the choice,” she says, “but help them to figure out what they’re good at, what they enjoy.” Amy, for instance, enjoys several sports, including horseback riding, soccer, and field hockey. My parents have always been very supportive of all of my athletic activities. Because I have trouble remembering left from right, for instance, Mom even bought me a little ring for my left hand so I could quickly figure out where I should be on the soccer field when playing left wing.”

Experts also advise parents to make sports for their children a priority of their own. Try to arrange family time so that it includes your child’s sports activities, and support them with your presence at games and matches. When it’s necessary for your child to make time for testing or studying with tutors or reading specialists, try to schedule appointments around games and practices.

When helping your child to choose a sport, look at how dyslexia affects his or her own learning style, strengths, and weaknesses. Shawn tried karate for a while, but discovered that hand-eye coordination problems made that activity difficult for him. Amy finally settled on swimming as her favorite sport, and the one at which she excelled. “I was good at listening to and applying the things my coaches said. If they said ‘hold your elbows this way’ I did it—and remembered it each time. Also,” she laughs, “in a swimming pool with clearly marked lanes, you always know exactly where you’re supposed to be!”

Focus, Planning

Parents, teachers, experts and, of course, dyslexic kids and teens themselves have described other benefits of playing sports. Both Dey and Cotter, for example, note that regular physical activity can enhance concentration and focus, improve mood, and help to relieve the kinds of stress that can beset any overscheduled, struggling student. Here Cotter quotes part of his school’s philosophy: “a healthy, disciplined student makes the best pupil.”

Playing sports can help to motivate a student to improve the kind of organizational skills they also need to succeed academically. Cotter says, “One of my rowers recently figured out that rowing and writing a paper both require planning ahead—making sure you have all your equipment before a competition is like making sure you have all your research outlined before you start writing—and that he had had to learn how to balance the time and attention required to succeed at both of these aspects of his life at the school. He also figured out that the time required for traveling to and from races to study presented an opportunity for him to do his homework.”

James, a high school senior for whom baseball is almost as important as his academic work, says that playing ball has helped him to hone a thoughtful and creative approach to both athletics and academics. “Baseball’s a cerebral sport in some ways,” he says. “To play ball well it helps to be able to step back and see the whole game, not just individual plays. I’m good at being able to detect patterns in the play, in the pitches, and so on, and some of that transfers to my academic work as well.”

Sports can also improve relationships with teachers and specialists who may be more likely to view and treat the child as a whole person, not just a set of (possibly less than stellar) grades and scores. Shawn has come to appreciate the impact his standing on his high school’s swim team has had on the whole team, and on the way his teammates view him, but also notes that this makes it easier for him to collaborate with teachers and coaches. He was recently asked to teach some swimming classes himself, and is pleased by the trust and respect of his coaches reflected in that assignment.

The Sports Payoff

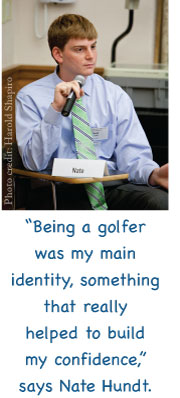

Nathaniel Hundt, a recent Yale graduate now working on environmental issues for the U.S. Department of the Interior, describes the role that being an enthusiastic golfer plays in his life. “I have always been a good writer,” Hundt says, “but my dyslexia makes reading a very slow process for me. I learned long ago that I need accommodations like extra time and a workspace free of distractions in order to complete a task successfully. Without these, I had a very hard time with tests—never finishing, not comprehending what I was reading.”

In 7th grade Hundt discovered golf, and quickly realized that he was remarkably good for his age. He played avidly, rising among the ranks of young golfers at golf tours throughout the mid-Atlantic region, where he grew up. “Being a golfer was my main identity, something that really helped to build my confidence,” he says.

Golf also helped Hundt to assess the way he approaches goals both on and off the green. “The same kinds of things I was good at in golf, I was also good at in school: I’m creative, I see the big picture, and I pursue my goals aggressively. My weaknesses affected both areas, too, though—if I rush, I make silly mistakes; if I don’t concentrate fully, I mess up. I’ve learned to take my time, envision the steps required to do what I need to do, and to focus on the task at hand.”

The most salient effects that sports participation has had on his life, though, says Hundt, are what he refers to as the intangibles. “Regardless of whether you have dyslexia,” he says, “You can’t be an athlete or a scholar unless you sort out your priorities and set limits, as well as goals, for yourself. In both, even when you’re competing against others, the key thing is that you’re always trying to perfect yourself.

Related

The Vocabulary of Dyslexia Diagnosis and Treatment

As a parent navigating dyslexia diagnosis and treatment for your child, you’ll want to become fluent in terminology school administrators and medical professionals use.

Read More

Choosing a School

If you have the luxury of being able to select a school for your dyslexic child, know that there are still questions to ask and considerations to make when you approach the school.

Read More

Preparing for Your First School Meeting

You see your child trying to read but unable to do so; it breaks your heart, and you want to do everything you can to make a real difference. Your goal is to help, and that often begins with talking to the school. Here are some tips to help you prepare.

Read More