Two Mothers’ Effort to Help Their Children Helped So Many More

How Two Moms’ Efforts to Help Their Children Changed the State of Kansas.

A group of Alphabetic Phonics students with their beloved teacher Robin Sipp

It was a bit like they’d raised the same puzzling child, a generation apart, in Wichita, Kansas. Each child would turn out to be profoundly dyslexic. But the path to diagnosis and remedy out of painful ignorance would be life changing for each mother. Those journeys would ultimately join together as a partnership that was way more powerful than either woman alone. Together, the two mothers would establish the Fundamental Learning Center (funlearn.org)—an organization that has provided nearly two thousand teachers the training to intervene on behalf of, and educate, some thirty-five thousand dyslexic children in Kansas, and counting. The center also offers educational evaluations, and in 2014, they added the Rolph Literacy Academy, the only school for dyslexic children in the entire state.

Where on earth did they get the gumption? Each mother was changed by her child. Jeanine Phillips by her son, Cooper, and Gretchen Andeel by daughter Katie. Jeanine Phillips recalled, “Cooper taught me everything I know about what kids need and how important it is that we stop everything to get them what they need. Through my son I overcame my own lack of confidence. It changed my life. It changed everything about it.”

Gretchen Andeel

Gretchen Andeel: “Everything I did was fueled by what happened to Katie. I never would have developed the strong feeling and empathy if it hadn’t been for Katie. I never would have had the nerve or the passion.” The youngest of her four adopted children, Katie was “smarter than a whip,” beautiful, funny, naturally athletic, and adored by her siblings. But, Andeel recalls, Katie “had her own language.” She didn’t enunciate clearly, and her words were sometimes a tossed salad of syllables. At four, despite an attentive private school, Katie couldn’t grasp the alphabet. A former teacher herself, Gretchen helped Katie memorize her ABCs at home, but that’s where Katie’s learning with letters stopped.

In first grade, it became clear Katie couldn’t read. Gretchen could barely contain her parental panic. As an educator, Gretchen had never learned what to do when the standard methods to teach reading failed. So Gretchen set about trying every learning “cure” late 1960s’ Wichita offered, no matter how goofy each seemed.

Gretchen hired the doctor who claimed juggling would somehow help Katie catch the reading code. A nun gave floor-crawling lessons to impart “left-right” brain dominance. Katie spent time doing “scotoptic sensitivity” behind different-colored eye lenses. Then there were repetitious tutors and a Sylvan learning center. None of them got Katie as far as the second page of Fun with Dick and Jane.

“I felt desperate. All that crazy stuff hadn’t killed Katie’s spirit—she woke up every morning thinking that that day would be the day she learned to read. But she’d come home frustrated, and she was hell on wheels. They were all teaching her sideways. No one in Wichita knew anything about dyslexia. Dyslexia just didn’t exist in Kansas.”

Then Katie’s school gave up on her—refusing to take her back for second grade. Gretchen tried Wichita’s other private school, to no avail. They wouldn’t even admit Katie to repeat first grade. “There was no real special ed in public school back then,” says Gretchen, so she was cornered. Nobody would even try to teach her child.

Katie’s luck turned because of a Texas teacher’s real-estate trouble. That teacher was trying to return home but couldn’t unload her house in Wichita, forcing her to remain at Katie’s private school. She happened to be the one who spotted Katie’s struggle and told Gretchen about a legitimate educational evaluator in Dallas.

Gretchen had little to lose besides the crackpot cures and the price of the plane tickets. He was the first psychologist who made sense. His diagnosis? Katie had dyslexia—profound dyslexia. Her problems all traced to what he called her language-based learning disability. Katie would need a teacher properly trained in remediating her dyslexia, and that training would have to come from out of state. It was simply not available in Kansas. Nor was schooling. Kansas was a dyslexia desert.

Gretchen Andeel found a willing teacher and paid for her training over several years while the teacher commuted as needed to Dallas. That teacher tutored Katie outside class during the accreditation process. The first huge payoff for Gretchen came one day in third grade when her Katie came home sporting a huge smile, with something important to tell her family: “I have great news,” she announced, “I am not dumb, I am dyslexic!”

In addition to the remedial teacher, Gretchen managed to spit and paste the rest of Katie’s elementary education together, doing battle with ignorance all the way. (Gretchen was even warned, “This dyslexia business is a cult.”) She spent summers recording her daughter’s textbooks on tape. She persuaded teachers to test Katie orally. She got the school to skip report cards. And a very young Katie flew to dyslexia camp in North Carolina all by herself at the end of third grade. All of it got Katie reading, then improved on it.

Gretchen says, “A lot of days she got beaten down, but she got back up every time. Katie taught me about perseverance and the importance of being an advocate. She taught me to get up every morning and face the world…. I had to be her voice, and she taught me how to be someone’s voice. I had never had any real adversity in my life. I learned about the other side of the coin from Katie. She didn’t have a voice if I didn’t supply it.”

By the end of middle school and a second successful dyslexia camp back East, it was time to cut her losses in Kansas and send Katie off to the first of two private Eastern boarding schools that specialized in dyslexia. With Katie taken care of, Gretchen had more time to research and help other mothers of dyslexic kids as they came along.

Drs. Sally and Bennett Shaywitz (center and second from right) pictured with Jeanine (far right), Bill Phillips (far left), and Anita Jones (Jeanine’s Mom).

“I am a knowledge collector—a vacuum cleaner—for information. I’d begun attending International Dyslexia Association conferences for oxygen and support. I was committed. I had found the solution and I wanted to share it.” One of those mothers she shared with would be Jeanine Phillips. Jeanine was in such bad straits with son Cooper, she’d broken down sobbing at a country club luncheon. A mutual friend wrote Gretchen’s name and number on a hand towel in the ladies room. Jeanine went home and called immediately. Within minutes Gretchen was standing in her kitchen, hands on Jeanine’s shoulders, saying, “You have to save your son’s life. You’re the only one who can save his life. You have to go to Texas for the training.”

That was how they met.

Up until that moment, Jeanine’s son Cooper was so sickly and pale, Jeanine was secretly resigned to the assumption that he was dying of cancer. She had taken him to everyone anyonecould think of—with no answers. Cooper had had exploratory surgeries for the daily vomiting and headaches. He’d had a psychiatric workup for his inability to follow instruction or socialize in preschool.

Everyone seemed to agree Cooper was very bright, but his intelligence didn’t present in any of the usual ways. In fact, no one seemed to understand him outside his own family. Like Katie, Cooper had made up his own language. Teachers didn’t take to him. Preschools had dumped him.

By the time he started kindergarten in a Wichita public school, the focus on “Cooper’s problem” had shifted to learning. It seemed Cooper may have been throwing up at the sight of school. He was marched through the same Wichita parade of dubious practitioners: the juggler, the crawler, the colored lenses, an audiologist, an “eye tracker.” All collected their fees and dismissed him as unreachable. Like Gretchen, Jeanine had also been a teacher before motherhood. But the further afield the “professionals” got, the further away a cure for Cooper felt, too.

“I doubted myself as a mom, and as an educator,” says Jeanine. “ I was desperate. I thought, ‘I’ve done everything.’ By the time Cooper was seven, there’d been seventeen different specialists.” Then along came a first-grade reading specialist who told Jeanine she didn’t know if Cooper had dyslexia, but she knew an educational evaluator newly relocated from Florida. That doctor would have good news and bad news. He told Jeanine: “Cooper has a profound, profound reading disorder. He has dyslexia. But Kansas doesn’t recognize dyslexia. So the diagnosis will be no good. Therefore I don’t know what to tell you to do about it.”

Jeanine had momentary relief that Cooper would live, followed by a deep fog of dumbfoundedness at the state she was in—both logically and geographically. Certainly someone at Cooper’s school had to be reasonable. She took the testing to the school psychologist. While she was waiting, the principal emerged with Cooper’s paperwork and addressed her instead. “I’ve never seen a report like this,” she told Jeanine. “I don’t think it’s fair for you to think your child can learn to read.”

Jeanine found herself wondering how many parents had gone before her. “It was a huge moment for me. I realized the school wasn’t going to help at all. ‘Not ever going to read?’ How can you make that determination when a child is only six years old? But what are we going to do to get help into the school building?”

Gretchen, Jeanine and Tammy at the very beginning of Fundations Learning Center.

Before meeting Gretchen, Jeanine had been lost. In her mind, she was only pounding on an imaginary school door while her son suffered. She’d never been particularly religious—just a Sunday Methodist. But Gretchen’s influence and information were so unimaginably helpful, Jeanine saw her visit as a gift from God.

“I don’t know what her religion was—or [decades on] is—(laughs), but I knew this was God’s intervention in my life at this moment. This made me a strong believer.” From Gretchen’s side, God was not in the picture. In Jeanine she just saw the dynamo she’d been waiting for. She knew the dyslexic children of Kansas had enormous need, and she couldn’t get the job done alone. “I can’t remember if she was sobbing any harder than the rest of them,” says Gretchen with a smile. “Certainly Jeanine was distraught. We spent a lot of time talking and talking. I went back and put her bags in the car to go and take the training. I knew she was a doer, not a talker. And I, of course, preferred the talking…(laughs).

At school in Dallas, Jeanine had a vision one night during a thunderstorm. She’d never had one before nor since. “I saw it. Things were laid out for me. ‘You haven’t come for your own child. You have come for thousands and thousands of children.’ It spooked me, but it stayed with me.”

What Jeanine learned in Texas, she applied immediately to her first student—Cooper. Within a remarkably short period of time after starting remedial tutoring, Cooper’s vomiting and headaches vanished. He began to share with other kids. His first-grade teacher made room for mother and son to work behind a curtain on the school stage after recess each day. “Cooper was learning!” Jeanine says, “I realized, ‘Oh my God! He hasn’t been sick, he was no longer underweight.’ Everything relaxed.”

Their secretive arrangement continued quietly and successfully into second grade. As other dyslexic students needed Jeanine’s help, she added them to her roster. When one delighted parent inadvertently tipped off the principal by marveling at her child’s progress, the principal came down hard: she threatened to force Cooperout of the school immediately, on the sudden claim that he was “too learning disabled” to attend.

Jeanine found her normally cooperative self morphed into a mother so enraged, she held up her son’s evaluation and, shredding it in the principal’s face, told her, “I’ll see you in court, bring it on.” Not long after, Jeanine got a call from the school district coordinator barring her from the building entirely. Jeanine would ultimately get the principal transferred and the coordinator fired. But in the moment, she could not find a way into the due process system of the imposing Kansas Public Schools.

“I was shaking and crying so hard. I decided I am not fighting this anymore. It was pointless. I got Cooper transferred to a private school. In the private school, all of a sudden, I was a consumer. They wanted him. They were open to my tutoring. They let me teach him his language arts.”

Cooper went to the same school as Gretchen’s Katie did. After fourth grade, he was off to dyslexia camp in upstate New York. Jeanine remembers he returned home looking different. “What I learned,” he told her upon arrival, “is I’m not the worst dyslexic in the world!” He remained, however, the worst dyslexic Jeanine would ever meet.

By fifth grade, with at long last her Cooper launching, Jeanine Phillips could finally concentrate on getting her certification not just as a trained dyslexia teacher, but as a trainer of other teachers as well. She’d also earned her master’s degree in education on the side. And she’d not lost track of either her mission or Gretchen Andeel.

“As I said to Gretchen, you got me into this, now you’re coming along (laughs).” With their children set, the two women were free to collaborate on advocacy. Jeanine and Gretchen agreed that the ripple effect of teaching the teachers would help the most dyslexic children possible. In 2001, they opened their nonprofit Fundamental Learning Center as a training facility. Funlearn.org offered a full menu—from weekend courses in intervention, to full certification requiring years. The center also offered learning evaluations and literacy classes for children with dyslexia.

More than thirty years after Gretchen sought help for her daughter, funlearn.org launched the only place to go for help in the state. “Jeanine is the visionary,” says Gretchen. “I was the practical get-it-done gal with the community ties. She’d scatter the matter and I’d pick up the pieces.”

“Lucky I am not a perfectionist,” says Jeanine. “But I am an optimist, and I was on a mission. Build a center, teach the teachers, fund the literacy classes for the kids on a sliding scale. I thought, ‘The school board is going to love this!’ What neither Gretchen nor Jeanine anticipated was that fifteen years after funlearn.org opened its doors, it would still stand alone as the sole dyslexia resource in the state of Kansas. The Fundamental Learning Center only got a two-year honeymoon before school authorities dropped the hammer. “It was crushing when they turned on us,” says Jeanine.

Gretchen continues, “The superintendent started circling the wagons fairly early—they were threatened by what we were doing…. We’d get discouraged. There were times when they came close to shutting us down—the school system gave us so much resistance.”

“That’s how we knew we’d started a movement,” explains Jeanine. The board of education’s toughest tactic was to keep the center’s trained teachers out of the public schools. The center was never again able to get them back in. Their teachers were limited to private tutoring roles.

The Wichita school superintendent also intimidated families by charging children who left school grounds for reading instruction with truancy. The center, according to Jeanine, eventually helped get the superintendent fired. But the damage was done.

Children from a Fundations class.

Their literacy class dwindled to twelve kids. Funlearn.org had to switch focus to survive. They concentrated on teachers from private and parochial schools. They developed one of the largest homeschooling training markets in the country. As far as Jeanine and Gretchen were concerned, the Kansas Board of Education was deliberately denying dyslexia, and it still is.

Though dyslexia is the most common learning disability and affects as many as twenty percent of all students (an estimated 100,000 students in Kansas), Jeanine says it is still dealt with as a “medical” diagnosis—not automatically triggering an educational solution. According to the national Advocacy Institute, Kansas is not the only state denying dyslexia in one form or another. Says spokeswoman Candace Cortiella, “We have had evidence from several states that parents are experiencing deliberate ignorance on the part of governing bodies or refusal to recognize dyslexia as a diagnosis…. We think they are concerned that if they use the word, they are going to have to address the problem. They aren’t just concerned about money, they are also concerned about precedent.”

But it well seems Jeanine and Gretchen may have a point about their state. Even after a “Dear Colleague” letter went out to state boards of education in the fall of 2015 from the U.S. Department of Education, making clear that dyslexia is an appropriate diagnosis for the purposes of educational planning—the Kansas Board of Education told the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, “Dyslexia is not a category of disability under the (federal) Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, so is therefore not used in Kansas.”

That attitude has made the mission at funlearn.org much harder, lonelier, and more necessary than ever. When the center first opened the Rolph Literary Academy in 2014, they could only take in seven boys, and the school was in a strip mall—no playground in the parking lot. By 2015, school enrollment had swelled to thirty-five. And 2016 has marked the expansion to real space. The Fundamental Learning Center now has ten thousand square feet in a former public school.

“We made it because we were willing to put in the work,” says Gretchen. “If you took up a job you didn’t quit it…. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Gretchen Andeel has since retired. She promised Jeanine six years, gave her eight, and is past an age she wants printed. She admires what Jeanine has done in her absence. The center has long exceeded her courage.

“I wasn’t nearly as adventuresome [as Jeanine]. I’d have held us back. I’d never have started a school. I thought it was overwhelming. But I am glad they did it…. Jeanine is like a terrier. It would take eight people to replace her. But you always wish you had a bigger effect, that you could save them all. There is no reason Kansas can’t, except for unwillingness and ignorance.”

Taken at Open House for the new Center.

And the Kansas State Board of Education remains one of a handful of states that organize their BOE as a separate wing of government—giving it power sometimes unchecked even by the state legislature. For Kansas parents, that can present an exhausting series of individual appeals on behalf of a dyslexic child while the critical years for literacy intervention waste away.

Jeanine Phillips finds this scandalous. She has inquired at the federal Justice Department about taking on the state for systematically denying the educational rights of dyslexic students. In the meantime she lobbies for school choice. She’ll try anything to shake things up. But her hopes for the public schools in her state are limited. As she testified before the legislature:

“Dyslexia remains the “d” word in this state, leaving thousands of parents and educators confused and, worse yet, blaming children who aren’t neurobiologically organized to associate spoken language to the printed system we use to read, write, and spell. We are losing.”

The motto of the Fundamental Learning Center is, “All children reading. All children succeeding.” Jeanine Phillips will never give up on that goal. But after decades of advocacy, the advice of both her and Gretchen to any new parent of a dyslexic child is dismal. Their first suggestion? Get the heck out of Kansas.

Related

Support From A High Profile Dyslexic

California Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom has been outspoken about his dyslexia and often takes time to meet with …

Read More

Older Kids Making A Difference

Often, older children feel especially grateful to the work of YCDC in illuminating their dyslexia. Above, B, now …

Read More

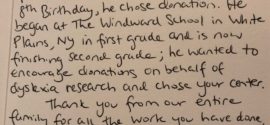

A Birthday Surprise for the Center

We recently received a lovely note from a parent whose child is dyslexic. Instead of asking for birthday …

Read More

Baking For Change

One young student even baked homemade “Twinkies” and sold them online, on his own, to raise money for …

Read More