Henry Winkler, Director & Actor

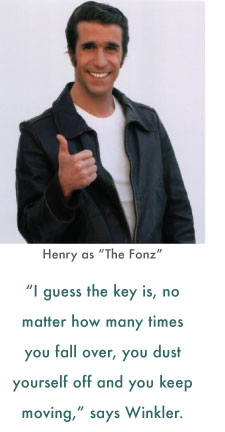

Henry Winkler has appeared on both the big screen and the TV screen, on stage, and behind the camera. Perhaps to many of us living in the 1970’s and ‘80s, he’ll forever be remembered first as the leather-jacket wearing, motorcycle-riding Arthur Fonzarelli, AKA, the “Fonz.” But Henry Winkler went on to produce television shows, like the very successful and popular show, MacGyver; direct several movies; and act in Neil Simon’s play, The Dinner Party, among others. He also pens the popular Hank Zipzer series, with co-author Lin Oliver, about the adventures and misadventures of the ever resourceful, but struggling student named Hank. Henry and Hank have a lot in common, mostly because the books center around the real-life experiences of Henry Winkler. Despite being bright, both of them found school very difficult, no matter how much they wanted to do well. That’s because both of them have dyslexia—something that Henry didn’t discover about himself until he was 31.

Henry grew up in New York City, with parents who were strict and stern, to say the least. “My parents were very, very, very, very, very short Jews from Germany,” Henry explains. “They believed in education. They thought I was lazy. I was called lazy. I was called stupid. I was told I was not living up to my potential. And all the time inside I’m thinking, I don’t think I’m stupid. I don’t want to be stupid. I’m trying as hard as I can. I really am. I was grounded for most of my high school career. They thought if I stayed at my desk for 6 weeks at a time, I was going to get it and they were just going to put an end to the silliness of my laziness. That was going to be that.”

Ironically, Henry found himself doing a lot of the same things when his stepson Jed was struggling with a report on his trip to visit the Hopi Indians. “He wrote two sentences. He erased a hole right through the paper. I sent him back to his room and said everything to him that was said to me: ‘come on, live up to your potential, you’re so verbal, this is silly that you’re not doing this. You cannot listen to Duran Duran, you can’t listen to your records, television is out—until you write your report.’” Henry and his wife had Jed tested, and when Jed was diagnosed with dyslexia, a light bulb went off for Henry. “I went, ‘Oh my goodness. I have something with a name.’ That was when I first got it.”

There was a reason why he encountered so many obstacles in school, and did not meet his parents’ expectations of being a straight-A student. They also expected him to run his father’s business. While Henry had every intention of doing well in school, he never intended to work with his father—he knew he wanted to be an actor from early on. “But it was a catch-22,” he says, “Because in middle school and high school you could only be in the play if you have a certain grade average. That grade average was way beyond my reach.”

It wasn’t that Henry wanted to be a poor student, but his then undiagnosed dyslexia made it just about impossible to excel in school no matter how hard he studied. “You want so badly to be able to do it and you can’t. And no matter how hard you try, it’s not working. You sharpen your pencils. You reinforce your lined paper with those gummy reinforcements. All your notebooks are all neat. You’ve got your dividers for all your subjects. You’re doing everything you can do to be in control and you have no control over your brain. It is painful.”

“I would study my words. I would know them cold. I would know them backwards and forwards. I would go to class. I would pray that I had retained them. Then I would get the test and spend a lot of time thinking about where the hell those words went. I knew them. The must have fallen out of my head. Did I lose them on the street? Did I lose them in the stairwell? Did I lose them walking through the classroom doorway? I didn’t have the slightest idea of how to spell the words that I knew a block and a half away in my apartment the night before.”

Becoming An Actor

Fortunately, Winkler’s spirit and confidence were resilient. He made it through school, even completing an MFA from the Yale School of Drama in 1970. But getting an acting job was another matter, especially since reading lines is a key part to the audition process. Henry found ways to cope, though. “You learn to negotiate with your learning challenge. I improvised. I never read anything the way that it was written in my entire life. I would read it. I could instantly memorize a lot of it and then what I didn’t know, I made up and threw caution to the wind and did it with conviction and sometimes I made them laugh and sometimes I got hired.”

Fortunately, Winkler’s spirit and confidence were resilient. He made it through school, even completing an MFA from the Yale School of Drama in 1970. But getting an acting job was another matter, especially since reading lines is a key part to the audition process. Henry found ways to cope, though. “You learn to negotiate with your learning challenge. I improvised. I never read anything the way that it was written in my entire life. I would read it. I could instantly memorize a lot of it and then what I didn’t know, I made up and threw caution to the wind and did it with conviction and sometimes I made them laugh and sometimes I got hired.”

He went from audition to audition until he landed a role that would bring him great success, and worldwide recognition as the extroverted, extra confident, and extra cool teenager Arthur Fonzarelli on Happy Days. “The Fonz” was supposed to be a small part when Henry first started, but his charisma and energy soon made his character a star. Despite Arthur Fonzarelli’s apparent ease on the screen, Winkler was anything but self-assured with the script. It took him two days to read and review his lines, and even then he improvised his lines because he couldn’t remember the script he so carefully worked on once he was in the studio. But he got the essence of it and ran with it. The hard work paid off, and earned him two Golden Globe awards for best actor. “I guess the key is, no matter how many times you fall over, you dust yourself off and you keep moving,” he tells Marie Speed of Success Magazine.

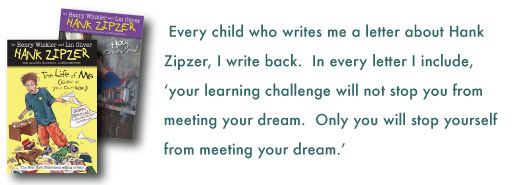

Winkler has indeed kept moving, and taking on his learning challenge, embracing it, and working with it. “You accept your learning challenge. I’m still frustrated by my learning challenge and I’m still smacked in the face by it every day,” he says. He also emphasizes, “This is what I know: A learning challenge doesn’t have to stop you. Every child who writes me a letter about Hank Zipzer, I write back. In every letter I include, ‘your learning challenge will not stop you from meeting your dream. Only you will stop yourself from meeting your dream.”‘

In multiple ways, Winkler practices what he preaches. In 1999, the celebrated playwright, Neil Simon asked him to read for his play, The Dinner Party. This was an honor that could easily turn into an embarrassment for someone who struggles to read “cold” and often improvises his lines. “My first impulse was to say, ‘thank you very much, but I’m busy,’” Henry recalled. “I then thought to myself, ‘oh my goodness; how can you say no? How could you possibly turn this down?’ And then I said to myself very easily, ‘you can’t do this, you’ll be out of the business, you’ll be out of your life. Aside from this, you’ll be embarrassing yourself into oblivion.’” He decided to do it anyway. He asked for the script early and read it every day. Simon asked him to be in the play. It started in LA and went all the way to Broadway. “Can you imagine if I had given into my fear,” Henry marveled.

“You don’t have any idea how powerful you are and what you can achieve. You literally cannot give in to your fear. You literally have got to walk over it, step on it’s face and keep moving toward where you want to go and eventually, if I can get there, there’s no reason you can’t get there.” Henry emphasizes this to his young readers, especially, but everyone, no matter how old or young, can use this as a mantra throughout life.

In addition to overcoming the struggles and the pain of being dyslexic, he also recognizes his strengths and gifts that come from it. Like his character, Hank, Henry is a problem solver. He can also see the big picture, and use it to help his friends. Like other dyslexics, he feels that “sixth sense,” that ability to sense things that are not said and really have a handle on who he is. “If you are able to communicate your feelings you can speak an international, very articulate language,” he tells the audience of the 1988 Conference of Orton Dyslexia Society in Los Angeles. “My friends would have social problems, and since I took most of my cues from the physical world around me, I was able to sit with them and tell them how they got into the problem, what it was doing to them, and how they could get out of trouble. I had no idea how I know this stuff, but lots of times I was right and it felt very good that I was able to do something for them!”

In addition to overcoming the struggles and the pain of being dyslexic, he also recognizes his strengths and gifts that come from it. Like his character, Hank, Henry is a problem solver. He can also see the big picture, and use it to help his friends. Like other dyslexics, he feels that “sixth sense,” that ability to sense things that are not said and really have a handle on who he is. “If you are able to communicate your feelings you can speak an international, very articulate language,” he tells the audience of the 1988 Conference of Orton Dyslexia Society in Los Angeles. “My friends would have social problems, and since I took most of my cues from the physical world around me, I was able to sit with them and tell them how they got into the problem, what it was doing to them, and how they could get out of trouble. I had no idea how I know this stuff, but lots of times I was right and it felt very good that I was able to do something for them!”

Winkler’s positive impact goes even further and more widespread—to the children throughout the US and the UK who read his books, and even their parents and teachers. “We don’t write down to children, so everybody laughs when they read the book. But I know for a fact that they are also useful,” Winkler said. With seventeen in the series, more than three million copies of the Hank Zipzer books have been sold in the United States. Children have written to him asking, “How do you know me so well?” And parents have said, “Oh my god; my child has never read a book, and they have now read five of yours. They would never attempt reading before.” Henry knows of the pleasure that books can bring, despite the difficulty he has reading them. “Every book I read I have to read in hardcover and it has to be on my shelf so I can see it because every one of them is a triumph,” he says.

The kids feel that same exhilaration with Winkler’s books. That boost—that they can finish a book and know that they are not alone in their struggles—is something that Winkler feels is tremendously important. He observes that, “You cannot believe that you can never say enough about how fabulous a human being that child is in the world. Their self image is being eaten away like an insidious worm from the inside out by this feeling of inadequacy because their brain is wired differently.” While Winkler’s parents never took the time to support him until after he was successful, the goal here is for the parents and teachers of today to look at the whole child and realize that just because a child reads slowly and is a poor speller doesn’t mean he can’t go on to achieve great things. “I’m an actor, producer, director; I write children’s books; and I’m in the bottom three percent of people academically in America,” he says. “I am what I am. I do all these different jobs. I am dyslexic. I can’t spell. Doing math in my head is as if I were to speak Russian at this moment. I am what I am and I am pretty comfortable with who I am and how I got to where I am with my learning challenges.”

The kids feel that same exhilaration with Winkler’s books. That boost—that they can finish a book and know that they are not alone in their struggles—is something that Winkler feels is tremendously important. He observes that, “You cannot believe that you can never say enough about how fabulous a human being that child is in the world. Their self image is being eaten away like an insidious worm from the inside out by this feeling of inadequacy because their brain is wired differently.” While Winkler’s parents never took the time to support him until after he was successful, the goal here is for the parents and teachers of today to look at the whole child and realize that just because a child reads slowly and is a poor speller doesn’t mean he can’t go on to achieve great things. “I’m an actor, producer, director; I write children’s books; and I’m in the bottom three percent of people academically in America,” he says. “I am what I am. I do all these different jobs. I am dyslexic. I can’t spell. Doing math in my head is as if I were to speak Russian at this moment. I am what I am and I am pretty comfortable with who I am and how I got to where I am with my learning challenges.”

Editor’s note: The publication of the 17th Hank Zipzer novel, A Brand-New Me!, marks the end of the series, with the graduation of Hank Zipzer from PS87 to middle school. What’s next for Hank? Well, first he has to pass tests to see what middle school he will attend—something where his dyslexia could get in the way. Knowing Hank, he’ll come through with flying colors, despite being a slow reader.

Related

Nelsan Ellis, Actor

Nelsan Ellis almost didn’t find the Juilliard Drama School because he kept misspelling the search term. Somebody in his Chicago high school told him he should go there.

Read More

Whoopi Goldberg, Academy Award-Winning Actress

She’s an Academy Award-winning actress, comedian, radio host, and television personality. She is one of the only ten people to win an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony Award; and is the first woman to be honored with the prestigious Mark Twain Prize for American Humor.

Read More

Brian Grazer, Academy Award-Winning Producer

At 64, self-made Hollywood mogul Brian Grazer has produced movies and television shows that have racked up 43 Oscar nominations, 138 Emmy nominations and grossed $14 billion. Just a few of his greatest hits include Apollo 13, Arrested Development, American Gangster, 8 Mile, 24, Frost/Nixon, Friday Night Lights, The Da Vinci Code, Parenthood, and the new show, Empire.

Read More

Jay Leno, Comedian & Television Personality

Jay Leno has been making humor out of headlines and everyday life since he was a kid. Even after his last night as the host of The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, a job he held for more than two decades, Leno plans to continue to perform in comedy venues across the country.

Read More