Fred Newman, Sound Engineer & Voice Actor

Fred Newman is an award-winning sound artist, actor, producer, comedian, and author. Newman is one of the two people behind the sound

effects that bring Garrison Keillor’s radio program A Prairie Home Companion to life. He’s been the voice of Harry in the movie Harry and the Hendersons, and also created sounds for other movies, including Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Practical Magic, and Gremlins, among others. He hosted the All-New Mickey Mouse Club and Nickelodeon’s Livewire, and created music and sounds for the animated series Doug. Younger audiences may know him from his word segments on PBS’s Between the Lions, for which he won three Emmys. Newman also revealed some of his secrets for creating sounds in his book MouthSounds.

Fred Newman makes a living out of being weird. If you’ve ever heard the sounds of squawking seagulls or the voices of those fast-talking salesmen pedaling their goods to Guy Noir on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, there’s a good chance that Fred Newman was the voice behind those sounds. Newman has also hosted or contributed to a variety of shows for children and teens, including the All-New Mickey Mouse Club and PBS’s Between the Lions, and provided sound, music and voices for the beloved cartoon Doug, about a somewhat awkward, but lovable pre-teen and his friends. He also created a sound piece for the National Park Service, depicting what Old Faithful would sound like from five miles below the surface to the top. From Newman’s vantage, what makes a person weird is what makes a person great. And what exactly helps make Fred Newman great? His dyslexia. In some way or another Fred Newman’s dyslexia paved the way for a checkerboard career that has entertained and educated a diverse population — from young to old, from NPR listeners to Nickelodeon watchers.

Fred Newman makes a living out of being weird. If you’ve ever heard the sounds of squawking seagulls or the voices of those fast-talking salesmen pedaling their goods to Guy Noir on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, there’s a good chance that Fred Newman was the voice behind those sounds. Newman has also hosted or contributed to a variety of shows for children and teens, including the All-New Mickey Mouse Club and PBS’s Between the Lions, and provided sound, music and voices for the beloved cartoon Doug, about a somewhat awkward, but lovable pre-teen and his friends. He also created a sound piece for the National Park Service, depicting what Old Faithful would sound like from five miles below the surface to the top. From Newman’s vantage, what makes a person weird is what makes a person great. And what exactly helps make Fred Newman great? His dyslexia. In some way or another Fred Newman’s dyslexia paved the way for a checkerboard career that has entertained and educated a diverse population — from young to old, from NPR listeners to Nickelodeon watchers.

“There is no negative connotation to dyslexia. You think and do things that no one else can do. . . . You’ve gotta have those people who think differently. They are leaders. They are the people who show us the light.”

Newman has been creating sounds and telling stories since he was a child growing up in Georgia. “I had a really loving family who as weird as I got — I was a very strange child — accepted and loved me. I did a lot of sounds. I was loud. I was boisterous. I’m sure there would be a lot of labels placed on me now. None of that was diagnosed at all,” he says. His father initiated the storytelling bug by encouraging his children to recreate the day’s events, sort of a dramatic-version answer to the question, “How was your day today?” Newman also sought out storytellers. “There was a store on the corner, and anybody who came in to have a Coca-Cola or a Big Orange would be sitting there eating their MoonPies and peanuts, and they’d just be telling stories. So that was where I would spend a lot of time. As a dyslexic — of course that word wasn’t used when I was young — having stories told to you was ideal. My mom would read to me, my teachers read to us. So I got the structure of the story, and the poetry of it, and the sounds of it — that’s where all my sounds come from.”

Although he loved stories, words, and learning, school meant struggling with memorizing math facts, getting tests and assignments done on time, and reading. “I made good grades, really because I would do what I needed to do,” he recalls. “I learned to play the game. I would turn things in on time. I did homework everyday. I always did that. My sister used to tease me, calling me a worrier because I was always worried about deadlines and stuff and I would leave notes to myself because I would forget things. But I would get things done, with some wear and tear on myself.”

Although he loved stories, words, and learning, school meant struggling with memorizing math facts, getting tests and assignments done on time, and reading. “I made good grades, really because I would do what I needed to do,” he recalls. “I learned to play the game. I would turn things in on time. I did homework everyday. I always did that. My sister used to tease me, calling me a worrier because I was always worried about deadlines and stuff and I would leave notes to myself because I would forget things. But I would get things done, with some wear and tear on myself.”

Newman made it through school by way of his own diligence and creativity. He learned to remember words through visualizing aspects of the word they described. “The word ‘look’ had two eyes in the middle of it. Then I saw ‘book.’ It looked like ‘look’ and you had to look at a book. And I saw that the bookends on either side of the word looked like the covers of the book. ‘Saw’ had the saw teeth — the ‘w’ was the saw teeth.” While he eventually learned to read by sounding out the letters of a word, it wasn’t until college that Newman discovered that not everyone saw words as he did — and he learned the name of what made him “weird.” “I took a psychology course, and I did some presentation. It must have been pretty full of leaps — the way my conversation does — and the professor said, ‘Have you ever been tested for dyslexia?’ I didn’t even know what it was. He did some tests, and said, ‘Yes, clearly you process in lumps, and you’re very nonlinear. I noticed that in your speech.”

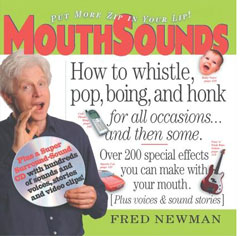

Newman graduated from college “by virtue of a lot of Post-it notes,” and worked as a blacksmith in Finland, and then as a carpet salesman in Texas, before deciding to go back to school. He enrolled in and graduated from Harvard Business School and landed a job at Newsweek magazine. While doing some stand-up comedy on the side, Newman saw how his sounds and different voices enhanced his stories and grabbed the audience’s attention. He thought people would be interested in making sounds themselves, so he wrote MouthSounds: How to Whistle, Pop, Click, and Honk Your Way to Social Success, which was published by Workman Publishing in 1980. When David Letterman had auditions for talent, Newman told his Newsweek boss that he was taking a bathroom break, and walked down the block to audition. “My book was coming out in about a month or so and when he said, ‘Come on the show,’ I went back to work and resigned. That was my last legitimate job. That was thirty years ago.”

Newman graduated from college “by virtue of a lot of Post-it notes,” and worked as a blacksmith in Finland, and then as a carpet salesman in Texas, before deciding to go back to school. He enrolled in and graduated from Harvard Business School and landed a job at Newsweek magazine. While doing some stand-up comedy on the side, Newman saw how his sounds and different voices enhanced his stories and grabbed the audience’s attention. He thought people would be interested in making sounds themselves, so he wrote MouthSounds: How to Whistle, Pop, Click, and Honk Your Way to Social Success, which was published by Workman Publishing in 1980. When David Letterman had auditions for talent, Newman told his Newsweek boss that he was taking a bathroom break, and walked down the block to audition. “My book was coming out in about a month or so and when he said, ‘Come on the show,’ I went back to work and resigned. That was my last legitimate job. That was thirty years ago.”

“Writing the book was my own dyslexic journey,” says Newman. “I realized that it was going to be a problem writing it. I didn’t type. Words were hard.” Newman discovered that a computer, although relatively new to the consumer market, would be the key to his success. He recalls, “Everything was paper so you had to think it out ahead of time, and then you would type it down and commit it to paper — very hard to erase — so you really wanted to think about what you were saying. For a dyslexic person to go that far ahead means thinking linearly, which is really difficult for me. But if you could see it on a screen and just back up and it wasn’t committed to anything, it was in hyperspace, that’s like my working memory. I could do that.”

“Whatever it is that makes you weird, that’s probably where your gifts are.”

In a nutshell, Newman knew what he struggled with and found ways to compensate, and learned how to use his strengths to carve out a unique niche — a very successful one at that. While on a television show for his book, his hilarious impression of a housefly landed him the job of host on the Nickelodeon show Livewire. From there, other shows followed, as did jobs doing sounds and voices for movies such as, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Practical Magic, and Gremlins I & II, and a variety of commercials. When he joined Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, Newman again struck upon a job that he not only loves, but at which he is quite good. “Everything about radio plays to my strengths,” he says. “I’m right there moment to moment. That’s where I am. I’m a good listener. I process quickly. Because I grew up with storytellers, I’m much more improvisational.”

Fred Newman has a talk he gives to young people he calls “Growing Up Weird.” In it he tells them, “Whatever it is that makes you weird, that’s probably where your gifts are.” Newman doesn’t come across as very weird, if you think of “weird” in the traditional sense — it’s not as if he wears a clown suit and makes funny faces. If weird means being incredibly fun, creative, smart, engaging, and original, everyone will soon want to be labeled as such. Reflecting on weirdness, dyslexia, and the people he admires, he remarks, “To me there is no negative connotation to dyslexia. You think and do things that no one else can do. In a culture you’ve gotta have those people who think differently. They are leaders. They are the people who show us the light. They’ve got the flashlights on the edges.”

Related

Nelsan Ellis, Actor

Nelsan Ellis almost didn’t find the Juilliard Drama School because he kept misspelling the search term. Somebody in his Chicago high school told him he should go there.

Read More

Whoopi Goldberg, Academy Award-Winning Actress

She’s an Academy Award-winning actress, comedian, radio host, and television personality. She is one of the only ten people to win an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony Award; and is the first woman to be honored with the prestigious Mark Twain Prize for American Humor.

Read More

Brian Grazer, Academy Award-Winning Producer

At 64, self-made Hollywood mogul Brian Grazer has produced movies and television shows that have racked up 43 Oscar nominations, 138 Emmy nominations and grossed $14 billion. Just a few of his greatest hits include Apollo 13, Arrested Development, American Gangster, 8 Mile, 24, Frost/Nixon, Friday Night Lights, The Da Vinci Code, Parenthood, and the new show, Empire.

Read More

Jay Leno, Comedian & Television Personality

Jay Leno has been making humor out of headlines and everyday life since he was a kid. Even after his last night as the host of The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, a job he held for more than two decades, Leno plans to continue to perform in comedy venues across the country.

Read More