David Flink, CEO of Eye to Eye

By Jane Wallace

“Alone we go fast, together we go far.”

– David Flink

David Flink (center) with an Eye-to-Eye mentor (left) and student (right)

At 34, David Flink is a man whose learning style and school experiences have determined his life’s mission. Flink is the co-founder of Eye to Eye, an innovative, effective program that matches up elementary and middle-school students with dyslexia and other learning disabilities (LD) with college-aged mentors who have the same. He knows firsthand how helpful a role model can be. He, too, has dyslexia and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); however, this social-movement leader prefers to be called an “LD/ADHDer,” or more simply, someone who thinks differently. He knows names matter. He has been called a lot of them.

The early labels isolated and shamed him—“stupid,” “crazy,” “lazy.” They started during his time at a Jewish day school in Atlanta. He was just a small child but the labels made him feel even smaller. Like every little kid with a learning issue he repeatedly heard perhaps the most confounding phrase, “Try harder.” Flink had no clue how he could work harder—he was already a very motivated young student. He figured it must be his fault, so he tried to cover over his failure and how much it hurt.

The only positive part about his first school was he could hide in the Hebrew language half of the day because nobody understood that. And he used the tissue trick. Whenever the risk of reading aloud rolled around, Flink fled for a Kleenex. But by fourth grade the school was closing in on his secret. He and his misunderstood dyslexia were “invited to apply elsewhere.”

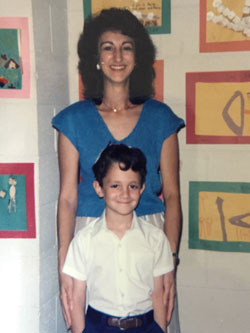

David and his mother

Flink remembers his mother searching for another school as if they had walked off the edge of the educational earth, but the Flink family had the geographic good fortune to live in Atlanta. Flink’s mother stumbled upon the progressive Schenck School simply because it was in their neighborhood and they were running out of options.

Schenck is a nationally renowned school for children with dyslexia. It was established before many educators knew the word. Flink was tested, diagnosed, and taught to read for the first time during the sixth grade. They spotted the Kleenex trick right off the top and parked a box on young David’s desk.

“When I arrived, I was overwhelmed by the camaraderie and support I felt from my teachers, as well as the other kids. Not only were the teaching methods appropriate to my way of thinking, but there were other kids just like me. It was the most at home I had ever felt.” Unlike many schools for learning disabilities, Schenck doesn’t want its students to stay. Instead, Schenck’s goal is to remediate learning lost to undiagnosed dyslexia, then direct students back out the door to mainstream schools.

Flink’s next school experience, however, was painful. He moved on to a pretentious college prep school where he paid for his hard-won straight A’s with relentless bullying by the “smart” kids. His self-esteem plummeted. It wouldn’t be the first time he wanted to believe he was “done” with his dyslexia.

But Atlanta’s rich educational resources rescued him again. This time the highly regarded Galloway School made a spot for the badly bruised freshman. Their flexibility and unflappable insight gave David the tools to figure out how to learn smarter, and how to get what he would need going forward. As Flink says:

“Galloway placed the problems in the environment rather than within the student…. If, for instance, I have to read something with my eyes, then I’m very disabled. But if I can read it with my ears (using a tape or iPhone), I am not disabled. This approach was essential to my understanding of my LD/ADHD. For the first time I was able to really own it.”

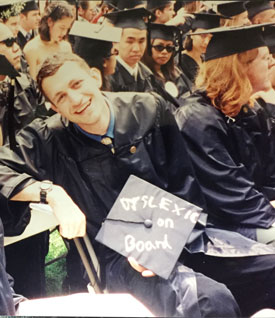

David at graduation. Note the saying on his mortarboard: “Dyslexia on board.”

During his elementary and high school years, David felt hopeless about his college prospects, worrying that no college would have him with his LD status, but his success at Galloway was more than enough to land him a spot at an Ivy League school. Once at Brown University, Flink was of two minds: he wanted to be “done” with his dyslexia—to be “done” insofar as how it interfered with his classwork—but at the same time, dyslexia was sowing the seeds of his future. While at Brown, David participated in a community-service project that brought together other peers with learning disabilities to tutor younger students with LD diagnoses. It brought to mind his earlier insecurities of not seeing a college future and thought that he would have been helped by learning from a role model who also had learning disabilities like the students he and his peers were tutoring.

Once at Brown University, Flink was of two minds: he wanted to be “done” with his dyslexia—to be “done” in so far as how it interfered with his classwork—but at the same time, dyslexia was sowing the seeds of his future.

After the community service project experience, Flink co-founded the program that would grow into a national movement: college students with dyslexia and other learning disabilities, like themselves, mentoring elementary and middle-school students. Eye to Eye now has sixty chapters in twenty states. “We are ambassadors of what is possible for students and young adults who learn differently, since we have walked in their shoes and can now effectively and uniquely pass on what we have learned to make their journey smoother and filled with success,” he says on the Eye to Eye website.

Although Eye to Eye originally began with tutoring in mind, the founders came to realize that wasn’t what the kids needed most. What the kids were lacking was the same thing that young David Flink was missing: successful models of people with dyslexia and the skills to emulate them. The middle schoolers also craved support for just being themselves. They were coming into the mentoring sessions having already suffered years of criticism.

“What we [now] know about self-esteem is that it is the most crucial part in learning. It trumps IQ, actually. When we focus on what kids are good at, it allows them to overcome what they are bad at… As we taught our students they were not broken, we learned we were not broken either.”

David Flink with the first chapter of Eye to Eye

Sixteen years on, Eye To Eye has developed and continues to use a unique, carefully crafted arts program for the mentoring sessions. Each middle schooler creates in such a way that they are engaged and encouraged to express themselves emotionally. It offers them an opportunity to show their frustrations, and their abilities. Art is something no kid can get wrong. Each student meets once a week with their mentor, but the mentors are also available in between, and for the rest of the students’ lives.

As the mentoring spreads, Eye to Eye has also expanded. It now runs a camp, a speakers’ bureau, a mentor alumni group, and events, including pop-up, street-team campaigns that call on teams to put a face on dyslexia and other learning disabilities in public. The speakers’ bureau, dubbed the “Think Different Diplomats,” is comprised of college-educated speakers doing outreach who literally “wear their LD on their sleeve.” Flink also published a new book for parents: Thinking Differently: An Inspiring Guide for Parents of Children with Learning Disabilities. He is determined to make the reality of dyslexia not a dark curse, just a need for informed accommodations. “We want the next generation to be empowered to make their environments work for them while fighting against the careless and discriminatory language that perpetuates stigma and low expectations…. Our kids don’t need to be ‘fixed’; they are not broken.”

One of Flink’s favorite expressions is, “Alone we go fast, together we go far.” He has gone from a struggling elementary-school student to an author and founder and CEO of an innovative organization and movement for bettering the lives of LD students. David Flink knows that he would not have been able to propel a movement forward without a solid foundation of his own.

Related

Keith L. Magee, Th.D., Pastor & Community Leader

As a young boy in rural Louisiana, Dr. Keith L. Magee learned the importance of giving back to make the world a better place. “My grandfather,” he said, “told me I had to pay rent every day for being on this earth. ‘If you don’t make a deposit,’ he told me, ‘no one can make a withdrawal.’” To ensure that he had plenty of time to make those deposits, Magee’s father woke him up every day at 5:30 a.m.

Read More