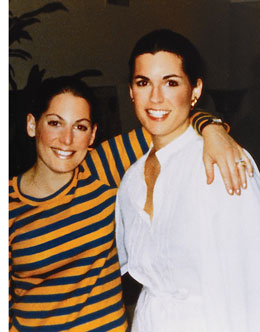

Nancy Brinker, Founder of Susan G. Komen for the Cure

Nancy Brinker is perhaps best known as the founder of the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation, now known as Susan G. Komen for the Cure. But that is only one of her many accomplishments. Brinker has also served as U.S. ambassador to Hungary and as White House Chief of Protocol and is currently the Goodwill Ambassador for Cancer Control for the United Nations World Health Organization. She is a board member of numerous organizations dedicated to expanding research and treatments for deadly and debilitating diseases and is co-author of the best-selling book Promise Me: How a Sister’s Love Launched the Global Movement to End Breast Cancer. Describing her as “a catalyst to ease suffering in the world,” Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honor.

Ambassador Brinker’s successes belie the frustration she experienced as a child in Peoria, Illinois, where she recalls struggling with “reading, spelling, all of it. I also had real trouble with math because I couldn’t understand the symbols,” she says. “It was like a foreign language to me. I was always daydreaming and doodling because I wasn’t following the drift of what the teacher was trying to say, unless she spoke slowly and dramatically or told stories and wrapped a context around them.” Despite her difficulties, Brinker appeared to be a good student. “My parents thought I was very bright because I did well on tests,” she says. “They didn’t understand that it was because I was a good memorizer. I knew I had to memorize the material, and you could logically kind of assume what would be on the exam, but standardized tests like the SAT were like hieroglyphics to me. And those logic questions and word problems I just literally could not do.”

Ambassador Brinker’s successes belie the frustration she experienced as a child in Peoria, Illinois, where she recalls struggling with “reading, spelling, all of it. I also had real trouble with math because I couldn’t understand the symbols,” she says. “It was like a foreign language to me. I was always daydreaming and doodling because I wasn’t following the drift of what the teacher was trying to say, unless she spoke slowly and dramatically or told stories and wrapped a context around them.” Despite her difficulties, Brinker appeared to be a good student. “My parents thought I was very bright because I did well on tests,” she says. “They didn’t understand that it was because I was a good memorizer. I knew I had to memorize the material, and you could logically kind of assume what would be on the exam, but standardized tests like the SAT were like hieroglyphics to me. And those logic questions and word problems I just literally could not do.”

Brinker’s abysmal performance on the SATs was a wake-up call to her parents, who never suspected she had a learning disability. But because she placed in the top 10 to 25 percent of her high school graduating class, she was accepted at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “It was very large and it was very tough for me there, and I spent more time outside of class than in,” she recalls. “There were often as many as 100 of us in a room with a black and white television and a professor talking. We also didn’t get much exposure to our teachers, and only a couple of them were memorable, but I did the best I could, by memorizing.” A sociology major with a double-minor in philosophy and English, Brinker taught herself a lot by reading historical biographies, which she continues to enjoy.

It was not until her son was diagnosed with dyslexia, in the fourth grade, that Brinker connected the dots to her own disability. “I was never officially diagnosed,” she says, “but I know I have it. I was always aware that I learned things differently from other people. I think it’s an auditory-processing problem, and my son has the same thing. I didn’t learn well in a classroom. I’m a visual learner and I’ve always learned better by doing and by experiencing.” Brinker’s son received the help he needed at a school that specialized in dyslexia and other learning problems, which were not widely understood when Brinker was a child.

“Maybe that’s why I’m an achiever,” she says. “I just wanted to understand, to strive to get over my learning disability. I just did what I could do. I think it made me stronger to have to struggle with learning problems when I was young. I also think it’s those things that happen to you when you’re young that shape you as you get older.” Another ingredient that helped shape Brinker were the examples her parents set for her and her sister as contributing members of their community. Each Saturday, when they were young, their mother would take them to volunteer for a local organization or activity. When they complained, she told them it was up to them “to fix what was wrong in this country.” She also discovered at a young age her strengths as “kind of an activist. I’m able to convene, and in some cases to lead, people,” says Brinker.

That strength certainly came to the fore when her sister, Susan, became ill with breast cancer and died in 1980, at age 36. Having promised Susan that she would do everything she could to end breast cancer forever, Brinker founded the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation two years later. At the time, she said, no one talked about the disease, corporations avoided sponsoring events relating to cancer, and there were no 800 numbers or Web sites providing information on it to patients and their families. Today, Susan G. Komen for the Cure has invested more than $2 billion in breast cancer research, education, screening, and treatment and enlisted more than 200 corporate sponsors in its efforts. And each year, over 1.5 million people, in more than 120 U.S. cities and 13 countries, participate in the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure, the world’s largest educational and fundraising event for breast cancer.

That strength certainly came to the fore when her sister, Susan, became ill with breast cancer and died in 1980, at age 36. Having promised Susan that she would do everything she could to end breast cancer forever, Brinker founded the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation two years later. At the time, she said, no one talked about the disease, corporations avoided sponsoring events relating to cancer, and there were no 800 numbers or Web sites providing information on it to patients and their families. Today, Susan G. Komen for the Cure has invested more than $2 billion in breast cancer research, education, screening, and treatment and enlisted more than 200 corporate sponsors in its efforts. And each year, over 1.5 million people, in more than 120 U.S. cities and 13 countries, participate in the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure, the world’s largest educational and fundraising event for breast cancer.

Brinker is gratified by her foundation’s success and considers it a tribute to the kindness and inspiration her older sister provided to her throughout her short life. “Susan was the sweetest, loveliest, and most charitable person in the world,” she says. “She was always doing for other people, and she was always so kind to me, even from the time we were little kids. She was always upbeat and cheerful and she taught me a lot about a lot of things, so it was a real tragedy for our family when we lost her. She left a husband, two children, and a community that loved her.”

In turn, Brinker would like to pass on to others some of the lessons she has learned about dyslexia. She advises children who are dyslexic to tell their parents early, so they get the help they need. “Your path will be different,” she says, “but that does not mean it will be bad. If you get it diagnosed and you understand what it is, life will be much more pleasant. You just can’t be discouraged because you’re a round peg that doesn’t fit in a square hole. You have to find the place you fit, and that means doing what you love. Everyone has something they do that they love. If you get to do something you love and if you practice it with a passion, you’ll be fine.”

Related

Tom Cavanaugh, Entrepreneur

Tom Cavanaugh was 71 before he saw his true reflection—not in a mirror—but in a movie. There he was, at 17, in a scene showing a high school student completely lost looking for his hallway locker, and then spinning the combination lock repeatedly, without result.

Read More

Ari Emanuel, Co-Chief Executive of William Morris Endeavor Entertainment

Emanuel learned at an early age to be aggressive and stand up for himself. Raised in a family where education was a high priority, he had to read the newspaper every day to keep up with current events and defend his political opinions each night at the family dinner table. This posed no problem for his brother Rahm, former Obama chief of staff and now Chicago mayor, and Ezekiel, a breast oncologist and head of the Department of Bioethics at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health. But for Emanuel, diagnosed in the third grade with dyslexia and ADHD, it was a monumental challenge. “I was on the ceiling,” he says. “The Ritalin helped, but reading was an enormous task.”

Read More

Daymond John, Entrepreneur

These days, Daymond John might be best known as one of the five savvy business executives (known as the “sharks”) who quickly mull over whether to invest their own money in the business ideas that budding entrepreneurs anxiously illustrate on the ABC hit television show Shark Tank.

Read More

Steve Mariotti, Founder & Former President of the Network for Teaching Entrepreneursh..

Mariotti, who dedicates over eighty hours a week to NFTE, learned the importance of persistence and hard work at an early age, when he was diagnosed with dyslexia. He struggled with reading, mispronounced similar sounds, and was unable to alphabetize.

Read More