Willard Wigan, Artist & Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire

“It began when I was five years old. I started making houses for ants because I thought they needed somewhere to live. Then I made them shoes and hats. It was a fantasy world I escaped to where my dyslexia didn’t hold me back and my teachers couldn’t criticize me. That’s how my career as a micro-sculptor began.”

Willard Wigan, Sculptor and Dyslexic

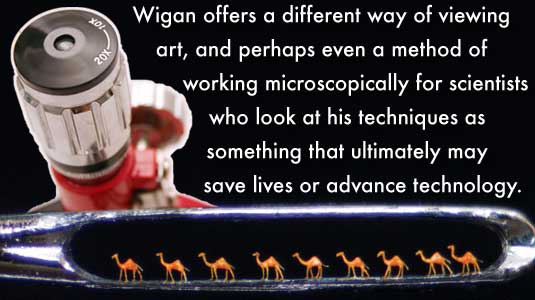

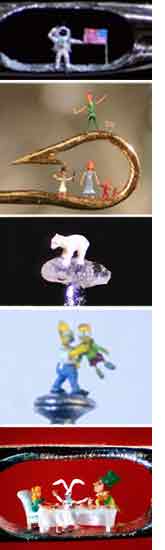

Many dyslexics have a remarkable ability to think outside the box; but artist Willard Wigan puts a twist on out-of-the-box thinking by crafting micro sculptures so tiny that many of them could fit inside a box—a very small box. He has recreated scenes from the bible, as well as from pop-culture, such as Homer Simpson holding Bart up in the air by the neck. Wigan’s art often occupy the eye of a needle, or like the Simpsons, the head of a pin. They are so small that they can only be seen with the help of a high-powered microscope. His ingenuity and unique perspective have earned him respect, appreciation, fame, and, well, a lot of money.

The respect and appreciation have been a long time in coming, considering that as a schoolboy growing up in 1960’s Birmingham, England, he was ridiculed by teachers and peers alike for not being able to read. No one talked about dyslexia in those days, and so young Willard’s learning problems went undiagnosed, and his teachers told him that he was stupid and would never amount to anything. They paraded him in front of the classroom, and when he could not do the work, one of his teachers pointed to him and explained to the class that, “Willard is an example of failure.”

The respect and appreciation have been a long time in coming, considering that as a schoolboy growing up in 1960’s Birmingham, England, he was ridiculed by teachers and peers alike for not being able to read. No one talked about dyslexia in those days, and so young Willard’s learning problems went undiagnosed, and his teachers told him that he was stupid and would never amount to anything. They paraded him in front of the classroom, and when he could not do the work, one of his teachers pointed to him and explained to the class that, “Willard is an example of failure.”

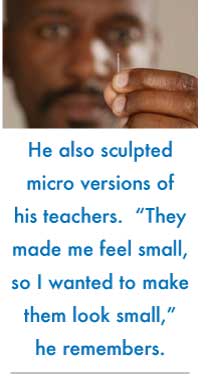

And so, at just 5 years old, Willard began to seek refuge from school and his unsympathetic teachers in a shed behind the garden. There he created his own worlds where he did not feel so small. It was in this shed where ants were his friends and his micro sculpting began. Young Willard worried that the ants were homeless, and so he built them tiny apartments to live and play in. And then he made teeny-tiny hats and shoes for the ants. Although the ants showed little gratitude and paid no rent, being an unpaid landlord was far better than being a ridiculed student. He also sculpted micro versions of his teachers. “They made me feel small, so I wanted to make them look small,” he says.

Wigan continued to sculpt miniatures from whatever he could find—splinters of wood, tiny pieces of glass, a single fiber from a shirt. His mother encouraged him to sculpt smaller and smaller pieces. She told him, “The smaller your work, the bigger your name.” But first, Wigan needed to find a way to make a living, which was complicated by his dyslexia, and his lack of schooling and reading and writing skills. “I couldn’t go to any place where I would have to read or write. I used to carry round a bandage to put over my hand if I had to fill in a form,” Wigan tells Robert Hardman of Britain’s Daily Mail.

As an adult, Wigan worked in a factory for two decades before making a name for himself. During that time, he sculpted at night, working on his miniatures. He also worked on being still and quieting his body—a must for his miniature sculptures and also for a job as a live mannequin for a clothing store. Ironically, turning a block of wood into a large bust of William Shakespeare is what got Willard and his miniatures noticed. He set up shop in an empty storefront at a shopping center, with the permission of the building’s manager, and began to carve. So remarkable was his carving that Wigan began to draw a crowd, including an art buyer, who offered him 500 pounds for the bust, and a reporter, to whom Wigan showed his miniature sculptures.

As an adult, Wigan worked in a factory for two decades before making a name for himself. During that time, he sculpted at night, working on his miniatures. He also worked on being still and quieting his body—a must for his miniature sculptures and also for a job as a live mannequin for a clothing store. Ironically, turning a block of wood into a large bust of William Shakespeare is what got Willard and his miniatures noticed. He set up shop in an empty storefront at a shopping center, with the permission of the building’s manager, and began to carve. So remarkable was his carving that Wigan began to draw a crowd, including an art buyer, who offered him 500 pounds for the bust, and a reporter, to whom Wigan showed his miniature sculptures.

Wigan has turned the pieces of a crushed up grain of sand into a polar bear; a bit of a nylon tag into Buzz Aldrin, and the end of a matchstick into the royal couple Prince Edward and Sophie Rhys-Jones, which he entitled, “Edward and Sophie: The Perfect Match.” He’s also crafted Peter Pan, Wendy, Tinker Bell, John and Michael on the tip of a fishing hook, and Alice, the Hare, and the Mad Hatter at a tea party. All characters from books he would struggle to read.

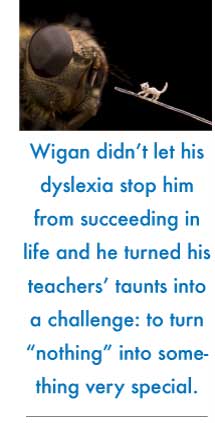

Wigan didn’t let his dyslexia stop him from succeeding in life and he turned his teachers’ taunts into a challenge: to turn “nothing” into something very special. “Just because you don’t see it, doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist,” he points out. In a sense, Wigan takes a bunch of what most of us would consider nothing, and turns it into something huge—once it its viewed through a microscope. He grabs fibers floating in the air and cobwebs from corners to turn them into works of art that are admired around the world.

Some of Wigan’s biggest admirers include British tennis player and entrepreneur David Lloyd, who owns a 70-piece collection insured for more than 20 million dollars; Sir Elton John; Magicians and Vegas entertainers Sigfried and Roy; and Prince Charles of Wales, who named him a member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his art. The Prince of Wales told Wigan that his work was “phenomenal,” and for the person who grew up hearing that he was a failure, “a moment like that means everything,” Wigan says. Other praise for Wigan’s work follows along the same lines, with some even calling it “The eighth wonder of the world.” Indeed, to even imagine that a shirt fiber could become the horns of a bull is really quite incredible. To be able to actually create this at the microscopic level, is on a whole other plane.

Some of Wigan’s biggest admirers include British tennis player and entrepreneur David Lloyd, who owns a 70-piece collection insured for more than 20 million dollars; Sir Elton John; Magicians and Vegas entertainers Sigfried and Roy; and Prince Charles of Wales, who named him a member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his art. The Prince of Wales told Wigan that his work was “phenomenal,” and for the person who grew up hearing that he was a failure, “a moment like that means everything,” Wigan says. Other praise for Wigan’s work follows along the same lines, with some even calling it “The eighth wonder of the world.” Indeed, to even imagine that a shirt fiber could become the horns of a bull is really quite incredible. To be able to actually create this at the microscopic level, is on a whole other plane.

While working under a microscope using homemade tools proves to be a frustrating challenge, Wigan continues the grueling process of creating his work because of the reaction he gets after someone views his finished pieces. He likes to see to look of awe in their faces, and he particularly enjoys it when people swear the first time they see his work. This “wow” factor means a lot to Wigan, especially after being told he would amount to nothing. “Now I’m showing how big nothing is,” he tells Washington Post Staff Writer DeNeed L. Brown. Not only is he showing how big nothing is, Wigan is also showing a different way of viewing art, and perhaps, even giving people in the technology and medical fields a method of working microscopically. Scientists are often baffled at Wigan’s ability to sculpt at the microscopic level, and look at his techniques as something that might ultimately save lives or advance technology.

In addition to his artistic gifts and potential gifts to science, Wigan also has a unique ability to take a sliver of a plastic cable tie and make it emerge into some of the most influential figures of our time. He also has a gift a lot of us wish for: patience. His sculptures often take a few months to complete, and in order to work on such a small scale, Wigan must have complete control over his body. He must slow his pulse down in order to be sure not to send his work in progress flinging into the air with just the pulsating beat in his thumb. And he also must make sure that he doesn’t breath in at the wrong time—a lesson that became pointedly clear when he inhaled Alice just before he placed her at the Mad Hatter’s table.

Instead of giving up on the piece, Wigan created a second Alice and finished the piece. “The second one I’d done was even better.” Just like his work, his view on setbacks and achievements is inspiring, especially for someone who looks to triumph over adversity. He sees a mistake as just a step in the path to success. “I’ve never actually failed, because when I work, I put a challenge to myself,” he tells NPR’s Liane Hansen in a radio interview. “I never really fail. If I fail, I come back again. And that’s how I always do it.”

Instead of giving up on the piece, Wigan created a second Alice and finished the piece. “The second one I’d done was even better.” Just like his work, his view on setbacks and achievements is inspiring, especially for someone who looks to triumph over adversity. He sees a mistake as just a step in the path to success. “I’ve never actually failed, because when I work, I put a challenge to myself,” he tells NPR’s Liane Hansen in a radio interview. “I never really fail. If I fail, I come back again. And that’s how I always do it.”

Related

John Behrens, Director of Photography

John Behrens is a 42-year-old self-taught director of photography who is much too busy to blow time on boredom. He’s a sucker for a good story, fiction or fact, and he loves capturing it on film. He’s shot movies, feature and television documentaries, television programs, commercials, concert films, and he lives to shoot more. Working for everyone, from Metallica to Tesla Motors to Disney Pictures, and almost every television or cable network, Behrens feels his dyslexia makes constant challenge fun.

Read More

Samuel Botero, Award-Winning Interior Designer

Samuel Botero knows two things for sure. One is that being Samuel Botero is not easy. The other is that you need a sense of humor in this life.

Read More

Jerry Pinkney, Children’s Book Illustrator

Before he became a legendary artist and illustrator of children’s books, gentle Jerry Pinkney was a little boy with a lot to do. By first grade he’d already figured out two important things: he had a gift with lines when it came to creating art, but an awful lag when those same lines formed letters for language.

Read More

Richard Rogers, Architect

Architect Richard Rogers is perhaps best known for designing iconic structures like the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Millennium Dome and the Maggie’s Centre in London and Terminal 4 Barajas Airport, Madrid.

Read More