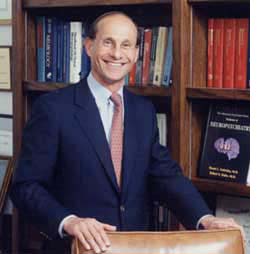

Stuart Yudofsky, M.D. Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Menninger Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine

Professor and Chairman of the Menninger Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine; Professor in the Menninger Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine; Consulting Staff, The Menninger Clinic, Houston, Texas.

Dr. Yudofsky’s research and clinical practice focus on two areas: psychopharmacology (the use of medications in the treatment of mental illnesses) and neuropsychiatry (the treatment of mood and behavioral changes associated with brain disorders such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury). For the past twenty years he has been editor-in-chief of the Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, the official journal of the American Neuropsychiatric Association, of which he has served as president. He is the author and editor of over forty medical books, including several of the standard textbooks in psychiatry and neuropsychiatry, over sixty book chapters, and numerous scientific articles.

Dr. Stuart Yudofsky has dedicated his career to helping people with mental illness. What few know is the dedication it took for Yudofsky, who is dyslexic, just to get through school. I was a very poor reader in elementary school through high school; my handwriting was terrible; and I had to spend a great deal of time keeping written letters and numbers in the proper sequences, he says. I and others like me are repeatedly told by teachers that we make careless mistakes, with the clear implication that we must not care enough about our work and that we are not trying hard enough to learn. Not only are we considered bad students, but, in our frustration, we begin to think that we are bad people. As the result of communications from teachers who are uninformed about dyslexia, I and many other students are taught by uninformed educators that we are not smart, not creative, and not useful.

Dr. Stuart Yudofsky has dedicated his career to helping people with mental illness. What few know is the dedication it took for Yudofsky, who is dyslexic, just to get through school. I was a very poor reader in elementary school through high school; my handwriting was terrible; and I had to spend a great deal of time keeping written letters and numbers in the proper sequences, he says. I and others like me are repeatedly told by teachers that we make careless mistakes, with the clear implication that we must not care enough about our work and that we are not trying hard enough to learn. Not only are we considered bad students, but, in our frustration, we begin to think that we are bad people. As the result of communications from teachers who are uninformed about dyslexia, I and many other students are taught by uninformed educators that we are not smart, not creative, and not useful.

Yudofsky can identify with the frustrations of young dyslexic students. Some have problems pronouncing words and saying words in their correct sequence. They are often ridiculed by people who can speak fluidly, and told they don’t know what they’re talking about. They become anxious in classroom settings, and fear being humiliated when called upon to answer questions.

While Yudofsky never heard the word dyslexia as a student, he discovered a way to overcome his reading problems while in the tenth grade. I began to look at words as a whole, rather than going through the syllables, he says. I taught myself how sentences are structured and how to get the gist of sentences and paragraphs rapidly. Paradoxically, I discovered that I loved reading, and became a voracious and devoted reader. Because I reversed numbers when I wrote them down, I learned how to do mathematical computations in my head, which also improved my speed of performance on tests. These adaptations, along with hard work, paid off, as he graduated from college with Phi Beta Kappa and Highest Honors in English.

While Yudofsky never heard the word dyslexia as a student, he discovered a way to overcome his reading problems while in the tenth grade. I began to look at words as a whole, rather than going through the syllables, he says. I taught myself how sentences are structured and how to get the gist of sentences and paragraphs rapidly. Paradoxically, I discovered that I loved reading, and became a voracious and devoted reader. Because I reversed numbers when I wrote them down, I learned how to do mathematical computations in my head, which also improved my speed of performance on tests. These adaptations, along with hard work, paid off, as he graduated from college with Phi Beta Kappa and Highest Honors in English.

Buoyed by his strengthened reading and test-taking skills, Yudofsky was admitted to Baylor College of Medicine. Because so many of the technical terms were new to me, I still had problems with my dyslexia. I compensated by devoting literally all my time to my studies. Many other students with dyslexia, however hard-working, may not be so fortunate. Because medical school entrance tests are highly competitive and time-limited, the students often feel very anxious and perform well beneath their knowledge and skill levels. They can apply for extra time to take the medical school entrance examinations, but very rarely is it granted, says Yudofsky. I believe this is true in many other types of professional schools, as well. I fear that countless young people with extraordinary potential are unable to gain access to professional schools because of their dyslexia. My hope is that with enhanced understanding of dyslexia will come increased accommodations on professional entrance examinations so that the very many deserving people with dyslexia will be given chances to pursue their dreams and to serve humanity.

Dr. Yudofsky’s three daughters, who were recognized by enlightened educators at early ages to have dyslexia, escaped the setbacks that their father experienced from the first grade onward. Instead of hearing that they were lazy or weren’t trying hard enough, they were told that their dyslexia was simply a brain difference that could be overcome by specialized learning techniques. They have all excelled academically, were or are about to graduate from Yale, where they achieved honors, and are doing well in their careers.

Dr. Yudofsky’s three daughters, who were recognized by enlightened educators at early ages to have dyslexia, escaped the setbacks that their father experienced from the first grade onward. Instead of hearing that they were lazy or weren’t trying hard enough, they were told that their dyslexia was simply a brain difference that could be overcome by specialized learning techniques. They have all excelled academically, were or are about to graduate from Yale, where they achieved honors, and are doing well in their careers.

Related

Beryl Benacerraf, M.D., Radiologist & Expert in Ultrasound During Pregnancy

A pioneer in radiology, particularly fetal ultrasonography, Dr. Benacerraf was among the first physicians to recognize the correlation between Down syndrome and physical signs, including an extra fold of skin on the fetus’s neck, as observed during an ultrasound. She is also the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine.

Read More

Blake Charlton, M.D., Author & Cardiologist Fellow at the University of California, S..

Blake Charlton would appear to have it all. A summa cum laude graduate of Yale University, a graduate of Stanford Medical School, and a published author, whose debut novel, Spellwright, was released to glowing reviews from the science fiction community and the publishing industry at large. The novel was the first of a nearly finished trilogy published by Tor Books. Set in a world where words can be physically peeled off a page and used to cast spells, Spellwright relates the misadventures of a wizard named Nicodemus Weal, who has a gift for producing magical language, but a disability that makes any text he touches misspell, with devastating consequences.

Read More

Delos “Toby” Cosgrove, M.D., Former President & CEO of Cleveland Clinic

Delos (“Toby”) M. Cosgrove, M.D., is president and chief executive officer of Cleveland Clinic. Under his leadership, Cleveland Clinic has experienced improved clinical outcomes and increased patient satisfaction, and expanded locally, nationally and internationally. Dr. Cosgrove has enacted policies focused on quality improvement, improved patient experience, and greater transparency and accountability at all levels of the organization.

Read More

Tyler Lucas, M.D., Chief of Orthopedic Surgery at Metropolitan Hospital & Lincoln Med..

Tyler Lucas is a member of the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society, an honor he received as a fourth-year medical student. He also received the Golden Scalpel award as a surgical resident for outstanding achievements in surgery. The impact that Dr. Lucas has on his patients’ lives is immeasurable. Many times, he is giving them their lives back, by restoring their freedom to move as they had before their injuries.